Jenkins–Traub algorithm

The Jenkins–Traub algorithm for polynomial zeros is a fast globally convergent iterative method published in 1970 by Michael A. Jenkins and Joseph F. Traub. It is "practically a standard in black-box polynomial root-finders".[1]

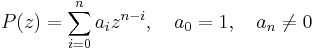

Given a polynomial P,

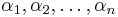

with complex coefficients compute approximations to the n zeros  of P(z). There is a variation of the Jenkins–Traub algorithm which is faster if the coefficients are real. The Jenkins–Traub algorithm has stimulated considerable research on theory and software for methods of this type.

of P(z). There is a variation of the Jenkins–Traub algorithm which is faster if the coefficients are real. The Jenkins–Traub algorithm has stimulated considerable research on theory and software for methods of this type.

Contents |

Overview

The Jenkins–Traub algorithm calculates all of the roots of a polynomial with complex coefficients. The algorithm starts by checking the polynomial for the occurrence of very large or very small roots. If necessary, the coefficients are rescaled by a rescaling of the variable. In the algorithm proper, roots are found one by one and generally in increasing size. After each root is found, the polynomial is deflated by dividing off the corresponding linear factor. Indeed, the factorization of the polynomial into the linear factor and the remaining deflated polynomial is already a result of the root-finding procedure. The root-finding procedure has three stages that correspond to different variants of the inverse power iteration. See Jenkins and Traub.[2] A description can also be found in Ralston and Rabinowitz[3] p. 383. The algorithm is similar in spirit to the two-stage algorithm studied by Traub.[4]

Root-finding procedure

Starting with the current polynomial P(X) of degree n, the smallest root of P(x) is computed. To that end, a sequence of so called H polynomials is constructed. These polynomials are all of degree n − 1 and are supposed to converge to the factor of P(X) containing all the remaining roots. The sequence of H polynomials occurs in two variants, an unnormalized variant that allows easy theoretical insights and a normalized variant of  polynomials that keeps the coefficients in a numerically sensible range.

polynomials that keeps the coefficients in a numerically sensible range.

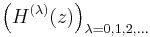

The construction of the H polynomials  depends on a sequence of complex numbers

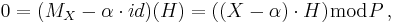

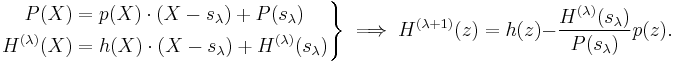

depends on a sequence of complex numbers  called shifts. These shifts themselves depend, at least in the third stage, on the previous H polynomials. The H polynomials are defined as the solution to the implicit recursion

called shifts. These shifts themselves depend, at least in the third stage, on the previous H polynomials. The H polynomials are defined as the solution to the implicit recursion

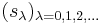

and

and

A direct solution to this implicit equation is

where the polynomial division is exact.

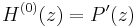

Algorithmically, one would use for instance the Horner scheme or Ruffini rule to evaluate the polynomials at  and obtain the quotients at the same time. With the resulting quotients p(X) and h(X) as intermediate results the next H polynomial is obtained as

and obtain the quotients at the same time. With the resulting quotients p(X) and h(X) as intermediate results the next H polynomial is obtained as

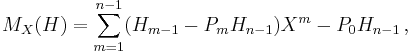

Since the highest degree coefficient is obtained from P(X), the leading coefficient of  is

is  . If this is divided out the normalized H polynomial is

. If this is divided out the normalized H polynomial is

Stage one: no-shift process

For  set

set  . Usually M=5 is chosen for polynomials of moderate degrees up to n = 50. This stage is not necessary from theoretical considerations alone, but is useful in practice. It emphasizes in the H polynomials the cofactor (of the linear factor) of the smallest root.

. Usually M=5 is chosen for polynomials of moderate degrees up to n = 50. This stage is not necessary from theoretical considerations alone, but is useful in practice. It emphasizes in the H polynomials the cofactor (of the linear factor) of the smallest root.

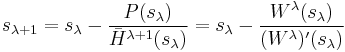

Stage two: fixed-shift process

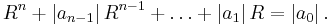

The shift for this stage is determined as some point close to the smallest root of the polynomial. It is quasi-randomly located on the circle with the inner root radius, which in turn is estimated as the positive solution of the equation

Since the left side is a convex function and increases monotonically from zero to infinity, this equation is easy to solve, for instance by Newton's method.

Now choose  on the circle of this radius. The sequence of polynomials

on the circle of this radius. The sequence of polynomials  ,

,  , is generated with the fixed shift value

, is generated with the fixed shift value  . During this iteration, the current approximation for the root

. During this iteration, the current approximation for the root

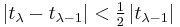

is traced. The second stage is finished successfully if the conditions

and

and

are simultaneously met. If there was no success after some number of iterations, a different random point on the circle is tried. Typically one uses a number of 9 iterations for polynomials of moderate degree, with a doubling strategy for the case of multiple failures.

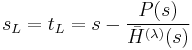

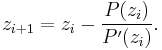

Stage three: variable-shift process

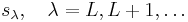

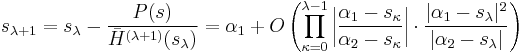

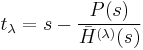

The  are now generated using the variable shifts

are now generated using the variable shifts  which are generated by

which are generated by

being the last root estimate of the second stage and

- where

is the normalized H polynomial, that is

is the normalized H polynomial, that is  divided by its leading coefficient.

divided by its leading coefficient.

If the step size in stage three does not fall fast enough to zero, then stage two is restarted using a different random point. If this does not succeed after a small number of restarts, the number of steps in stage two is doubled.

Convergence

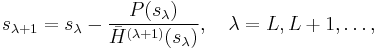

It can be shown that, provided L is chosen sufficiently large, sλ always converges to a root of P.

The algorithm converges for any distribution of roots, but may fail to find all roots of the polynomial. Furthermore, the convergence is slightly faster than the quadratic convergence of Newton–Raphson iteration, however, it uses at least twice as many operations per step.

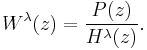

What gives the algorithm its power?

Compare with the Newton–Raphson iteration

The iteration uses the given P and  . In contrast the third-stage of Jenkins–Traub

. In contrast the third-stage of Jenkins–Traub

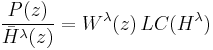

is precisely a Newton–Raphson iteration performed on certain rational functions. More precisely, Newton–Raphson is being performed on a sequence of rational functions

For  sufficiently large,

sufficiently large,

is as close as desired to a first degree polynomial

where  is one of the zeros of

is one of the zeros of  . Even though Stage 3 is precisely a Newton–Raphson iteration, differentiation is not performed.

. Even though Stage 3 is precisely a Newton–Raphson iteration, differentiation is not performed.

Analysis of the H polynomials

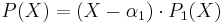

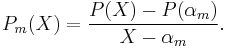

Let  be the roots of P(X). The so called Lagrange factors of P(X) are the cofactors of these roots,

be the roots of P(X). The so called Lagrange factors of P(X) are the cofactors of these roots,

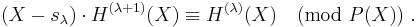

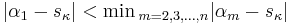

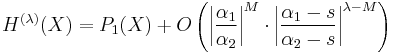

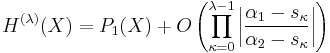

If all roots are different, then the Lagrange factors form a basis of the space of polynomials of degree at most n − 1. By analysis of the recursion procedure one finds that the H polynomials have the coordinate representation

Each Lagrange factor has leading coefficient 1, so that the leading coefficient of the H polynomials is the sum of the coefficients. The normalized H polynomials are thus

Convergence orders

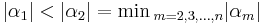

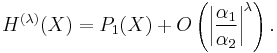

If the condition  holds for almost all iterates, the normalized H polynomials will converge at least geometrically towards

holds for almost all iterates, the normalized H polynomials will converge at least geometrically towards  .

.

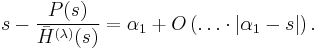

Under the condition that

one gets the aymptotic estimates for

- stage 1:

- for stage 2, if s is close enough to

:

:

- and

- and for stage 3:

- and

- giving rise to a higher than quadratic convergence order of

, where

, where  is the golden ratio.

is the golden ratio.

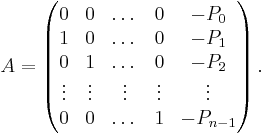

Interpretation as inverse power iteration

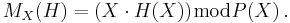

All stages of the Jenkins–Traub complex algorithm may be represented as the linear algebra problem of determining the eigenvalues of a special matrix. This matrix is the coordinate representation of a linear map in the n-dimensional space of polynomials of degree n − 1 or less. The principal idea of this map is to interpret the factorization

with a root  and

and  the remaining factor of degree n − 1 as the eigenvector equation for the multiplication with the variable X, followed by remainder computation with divisor P(X),

the remaining factor of degree n − 1 as the eigenvector equation for the multiplication with the variable X, followed by remainder computation with divisor P(X),

This maps polynomials of degree at most n − 1 to polynomials of degree at most n − 1. The eigenvalues of this map are the roots of P(X), since the eigenvector equation reads

which implies that  , that is,

, that is,  is a linear factor of P(X). In the monomial basis the linear map

is a linear factor of P(X). In the monomial basis the linear map  is represented by a companion matrix of the polynomial P, as

is represented by a companion matrix of the polynomial P, as

the resulting coefficient matrix is

To this matrix the inverse power iteration is applied in the three variants of no shift, constant shift and generalized Rayleigh shift in the three stages of the algorithm. It is more efficient to perform the linear algebra operations in polynomial arithmetic and not by matrix operations, however, the properties of the inverse power iteration remain the same.

Real coefficients

The Jenkins–Traub algorithm described earlier works for polynomials with complex coefficients. The same authors also created a three-stage algorithm for polynomials with real coefficients. See Jenkins and Traub A Three-Stage Algorithm for Real Polynomials Using Quadratic Iteration.[5] The algorithm finds either a linear or quadratic factor working completely in real arithmetic. If the complex and real algorithms are applied to the same real polynomial, the real algorithm is about four times as fast. The real algorithm always converges and the rate of convergence is greater than second order.

A connection with the shifted QR algorithm

There is a surprising connection with the shifted QR algorithm for computing matrix eigenvalues. See Dekker and Traub The shifted QR algorithm for Hermitian matrices.[6] Again the shifts may be viewed as Newton-Raphson iteration on a sequence of rational functions converging to a first degree polynomial.

Software and testing

The software for the Jenkins–Traub algorithm was published as Jenkins and Traub Algorithm 419: Zeros of a Complex Polynomial.[7] The software for the real algorithm was published as Jenkins Algorithm 493: Zeros of a Real Polynomial.[8]

The methods have been extensively tested by many people. As predicted they enjoy faster than quadratic convergence for all distributions of zeros.

However there are polynomials which can cause loss of precision as illustrated by the following example. The polynomial has all its zeros lying on two half-circles of different radii. Wilkinson recommends that it is desirable for stable deflation that smaller zeros be computed first. The second-stage shifts are chosen so that the zeros on the smaller half circle are found first. After deflation the polynomial with the zeros on the half circle is known to be ill-conditioned if the degree is large; see Wilkinson,[9] p. 64. The original polynomial was of degree 60 and suffered severe deflation instability.

References

- ^ Press, W. H., Teukolsky, S. A., Vetterling, W. T. and Flannery, B. P. (2007), Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing, 3rd ed., Cambridge University Press, page 470.

- ^ Jenkins, M. A. and Traub, J. F. (1970), A Three-Stage Variables-Shift Iteration for Polynomial Zeros and Its Relation to Generalized Rayleigh Iteration, Numer. Math. 14, 252–263.

- ^ Ralston, A. and Rabinowitz, P. (1978), A First Course in Numerical Analysis, 2nd ed., McGraw-Hill, New York.

- ^ Traub, J. F. (1966), A Class of Globally Convergent Iteration Functions for the Solution of Polynomial Equations, Math. Comp., 20(93), 113–138.

- ^ Jenkins, M. A. and Traub, J. F. (1970), A Three-Stage Algorithm for Real Polynomials Using Quadratic Iteration, SIAM J. Numer. Anal., 7(4), 545–566.

- ^ Dekker, T. J. and Traub, J. F. (1971), The shifted QR algorithm for Hermitian matrices, Lin. Algebra Appl., 4(2), 137–154.

- ^ Jenkins, M. A. and Traub, J. F. (1972), Algorithm 419: Zeros of a Complex Polynomial, Comm. ACM, 15, 97–99.

- ^ Jenkins, M. A. (1975), Algorithm 493: Zeros of a Real Polynomial, ACM TOMS, 1, 178–189.

- ^ Wilkinson, J. H. (1963), Rounding Errors in Algebraic Processes, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.

External links

- Additional Bibliography for the Jenkins–Traub Method

- Internet Resources for the Jenkins–Traub Method

- A free downloadable Windows application using the Jenkins–Traub Method for polynomials with real and complex coefficients

- CPOLY (Algorithm 419 from Comm. ACM) on Netlib. In Fortran.

- RPOLY Algorithm 493 from ACM TOMS) on Netlib. In Fortran.

- Online Calculator Online Polynomial Calculator using the Jenkins Traub procedure

![\begin{align}

\bar H^{(\lambda%2B1)}(X)

&=\frac1{X-s_\lambda}\cdot

\left(

P(X)-\frac{P(s_\lambda)}{H^{(\lambda)}(s_\lambda)}H^{(\lambda)}(X)

\right)\\[1em]

&=\frac1{X-s_\lambda}\cdot

\left(

P(X)-\frac{P(s_\lambda)}{\bar H^{(\lambda)}(s_\lambda)}\bar H^{(\lambda)}(X)

\right)\,.\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/438af38185731407712051198b0ec90e.png)

![H^{(\lambda)}(X)

=\sum_{m=1}^n

\left[

\prod_{\kappa=0}^{\lambda-1}(\alpha_m-s_\kappa)

\right]^{-1}\,P_m(X)\ .](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d162fe7990089b58ad1ff9a5819a62b1.png)

![\bar H^{(\lambda)}(X)

=\frac{\sum_{m=1}^n

\left[

\prod_{\kappa=0}^{\lambda-1}(\alpha_m-s_\kappa)

\right]^{-1}\,P_m(X)

}{

\sum_{m=1}^n

\left[

\prod_{\kappa=0}^{\lambda-1}(\alpha_m-s_\kappa)

\right]^{-1}

}

=\frac{P_1(X)%2B\sum_{m=2}^n

\left[

\prod_{\kappa=0}^{\lambda-1}\frac{\alpha_1-s_\kappa}{\alpha_m-s_\kappa}

\right]\,P_m(X)

}{

1%2B\sum_{m=1}^n

\left[

\prod_{\kappa=0}^{\lambda-1}\frac{\alpha_1-s_\kappa}{\alpha_m-s_\kappa}

\right]

}\ .](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/30b4ece3c60982c2f8a04ec0bd4b9314.png)